Interview with Mattia Piffaretti: Why Understanding Human Factors is Crucial When Freeriding?

Mathieu Ros Medina is passionate about mountain, ski and snowboard. He has over 15 years of experience as journalist in these fields.

Mattia Piffaretti holds a PhD in sports psychology and heads the AC&T Sport Consulting firm in Lausanne. He has worked with many national and international sporting federations on the mental preparation of athletes, coaches and referees, and he promotes health through sport. He is a sports psychology lecturer in the University of Freiburg Faculty of Medicine. In addition, he is a devoted supporter of WEMountain and a compelling and passionate speaker.

Mathieu Ros (MR): Do sports psychologists have to practise a sport to understand it? What’s your relationship to skiing?

Mattia Piffaretti (MP): Yes, I think we do. Sport experience is crucial in our field. I used to play competitive basketball at a high level. That gave me an insider’s view of sports psychology and team dynamics. As for skiing, from a very young age, I had the privilege of holidaying at resorts in the cantons of Grisons, Valais and Ticino. So it’s a very familiar environment, even if I’m mostly an on-piste skier. I love snowy landscapes, but I don’t have the experience to tackle backcountry slopes and face risks like rockslides or avalanches. When I was young, I went on mountain excursions, and the feeling of being exposed quickly forced me to come to terms with my inner strengths and personal limits.

MR: How did you learn about WEMountain and start building tools for their courses?

MP: In the early 2000s, near the start of my career in sports psychology, I became interested in extreme sports. Dominique Perret is a legend of a unique—and risky—style of skiing. I studied his strategies: how he prepared for situations that take you to limits that command respect and force you into self-awareness. Around the same time, I organized a conference on extreme sports for the Swiss Association of Sport Psychology. During a roundtable discussion, Mike Horn and Dominique Perret were asked about their motivations for thrill-seeking and accomplishing sporting feats. Nearly two decades later, I was able to apply those reflections and work to the WEMountain project when Dominique contacted me to better understand the human factors behind risk taking. Are there protective factors at play? Are any more likely to lead to risk taking? Those are the questions I was asking as I resumed my research to develop – alongside other experts – the tool that is now integrated into the WEMountain program.

MR: How do extreme sports compare to those practised by the high-performance athletes you work with?

MP: It varies. Obviously, danger is much more prevalent in some sports, and error can have far more serious consequences. Take sports that aren’t generally considered extreme, like downhill skiing. When a fifteen year-old selected for athlete development slaloms downhill at over 100 km/h in a Super-G, does that qualify as “extreme”?

Sailing or more generally any sport that pits people against the natural environment involves more risk. And we know that brain injury rates are high in contact sports like American football. All sports disciplines seek to balance prioritizing athlete health and allowing them to develop and push the limits. That’s a bit of a paradox, so having tools that help maintain that balance is key. And they leverage the same series of factors that WEMountain talks about: technology, knowledge, preparation, self-knowledge and emotional self-regulation. Achieving a balance between physical health and the very highest levels of performance is now possible! Just a decade or two ago, these notions were seen as contradictory—to push limits, athlete health had to be sacrificed.

Today, safeguarding has come to the fore in sports. The IOC has even developed training programs to help safeguard athlete health and protect them from forms of external and self-inflicted abuse in the name of performance.

MR: You differentiate between sports like sailing and downhill skiing that are practised in the natural environment and those that aren’t. When it comes to understanding risk in the mountains, the focus has often been on external factors like snowpack stability and mountain conditions, as if internal factors don’t exist. This change in perspective is very recent, isn’t it?

MP: You’re kidding yourself if you believe that technology, data and an understanding of the snowpack will protect you from all risk. We are starting to understand that human factors are responsible for 90% of situations that trigger avalanches or otherwise put a person at risk. Human factor refers to a person’s characteristics that affect how they filter and perceive information, take decisions and behave during outdoor activities. We built and expanded on that paradigm for WEMountain. It’s what will make a dent in the statistics and reduce the number of accidents.

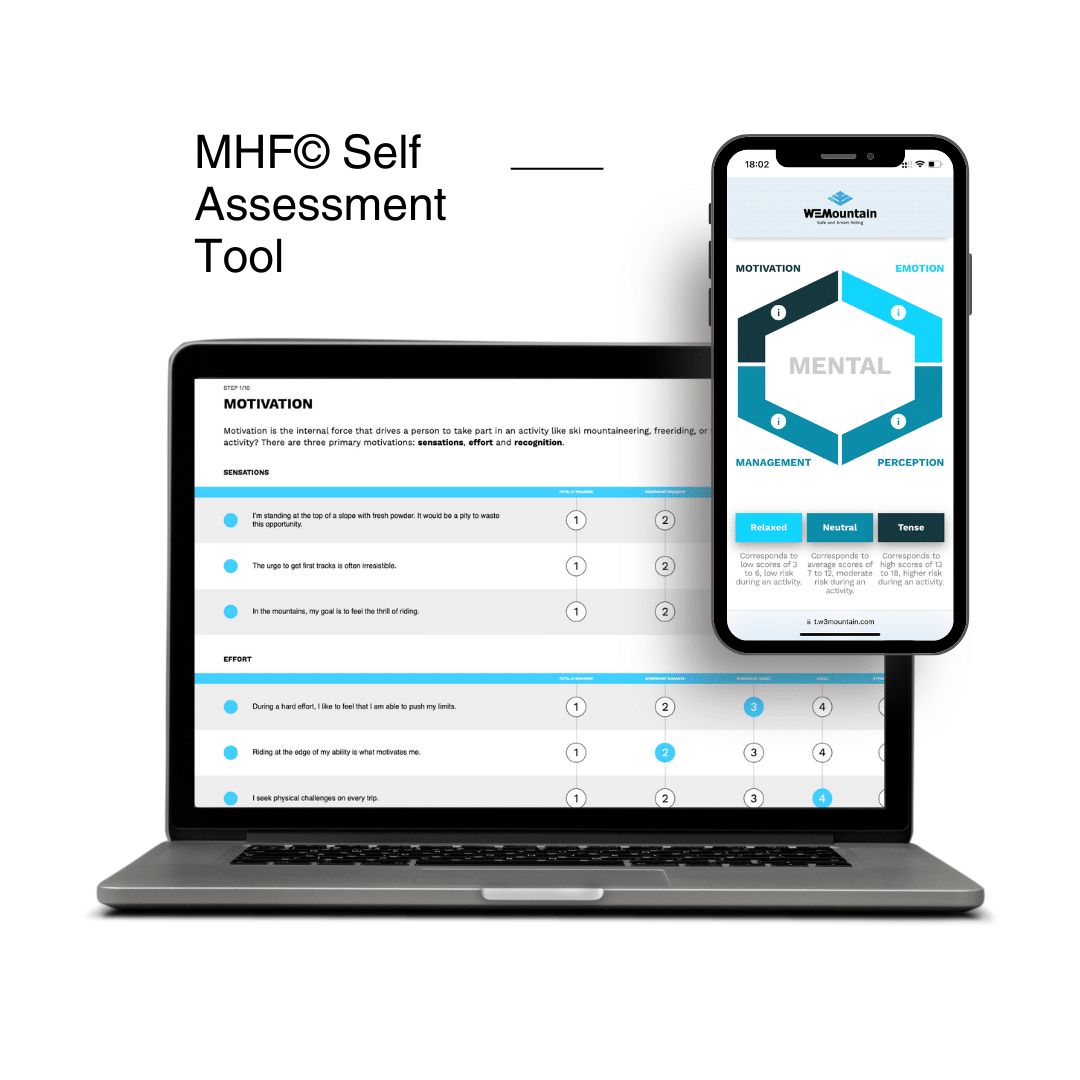

MR: You called this Mountaineering Human Factor, or MHF. Could you explain what that is?

MP: It’s a tool we based on the scientific literature and interviews with experts and members of the mountaineering community who shared specific real-life situations. Then we designed questionnaires for backcountry recreationists on typical scenarios. How would they react? What would they tell themselves? What would motivate them? Essentially, this tool assesses how human factors—emotion, motivation, perceptions of reality and cognitive biases—affect our actions in different situations. It demonstrates that all these factors influence how people face challenges and how specific behaviours and techniques can put them at risk or keep them safe.

MR: So it’s multifactorial. It depends on the condition of both the individual and the group, right?

MP: Group dynamics have a major effect on perception. They can help protect a group, but they can also amplify risk takingand are responsible for certain types of accidents, according to the literature. For example, skiers who stay too close together can repress their individual critical thinking skills, telling themselves, “I see something, but I don’t dare mention it because the group is going in that direction.”

MR: Those issues are well documented from a medical and human standpoint, but how is this put into practice?

MP: Our tool helps raise awareness and encourages self-reflection. It’s like standing in front of a mirror before heading out each morning and asking, “What’s my inner weather like today? How strong is my sense of urgency? What are my motivations? Am I going because I really want to or because I feel I have to?” Depending on the answers, a person may be more or less likely to put themselves in high-risk situations. So this mindfulness is crucial. Mental preparation is first and foremost about being aware of your resources. How do I feel? What skills do I have? What will I use? How can I get ready for a challenge without taking it too lightly? How can I take the time to patiently and carefully prepare my equipment but also, and more importantly, myself, my emotions, visualization, and backup plans? In competitive sport, this important prep work is becoming increasingly widespread.

MR: Everyone thinks about preparing equipment—backpack, gloves, water bottle, etc. But we often forget it’s important to prepare ourselves. After all, we’re the central figure.

MP: That’s exactly what we want to change. We’ve integrated this tool into WEMountain’s courses to encourage this vital self-reflection. In the future, we hope to introduce practical mindfulness tools that teach people slow down, breathe and not involuntarily give into often subconscious emotions and perceptions. These tools will help raise self-awareness and save lives. For now, the key is to educate people about human factors and coach WEMountain students on how to account for and control them.